The COVID pandemic sucked. There’s no getting around that. When you are an experimentalist with an experiment that is barely working and you are suddenly forced to work from home away from the laboratory, I took it as a challenge to learn a new skill. In this case it was coding with Python.

When I started my Marie Curie fellowship in the Leiden Observatory in 2019, I felt out of sorts in many ways. It seemed that everybody around me was working on Python, building beautiful programs to treat data from massive astronomical flagships like ALMA, Hubble, NOEMA, and eventually JWST as well.

Although completely derailing the immaculate plan I had made for my fellowship, I now had the opportunity to assimilate. But what good is a new skill if you are not going to use it?

Prior to arriving in Leiden, I had worked on measuring so-called ultraviolet photoionization cross sections at the SOLEIL synchrotron, e.g., the photoionization cross section of the mercapto radical SH (see below).

It so happens that the Leiden observatory hosts an international database of cross sections to be used for astrochemical modeling (mostly using Python). As my Leiden contract had been extended for a full year and having finished the laboratory measurements I had intended, I offered my services to Prof. Ewine van Dishoeck to update the database using multiple new cross sections that had been obtained either experimentally or theoretically in the previous years since the last database. It was also pertinent because our understanding of molecular complexity in space has been accelerating rapidly during this time and at the time of writing over 100 new molecules have been detected in various regions in space since 2017.

This update has now been implemented and the publication detailing all of the updates has now been formally published (Hrodmarsson & van Dishoeck 2023).

I would like to write a little about what these cross sections are. How are they used? How do they help us understand chemistry in space?

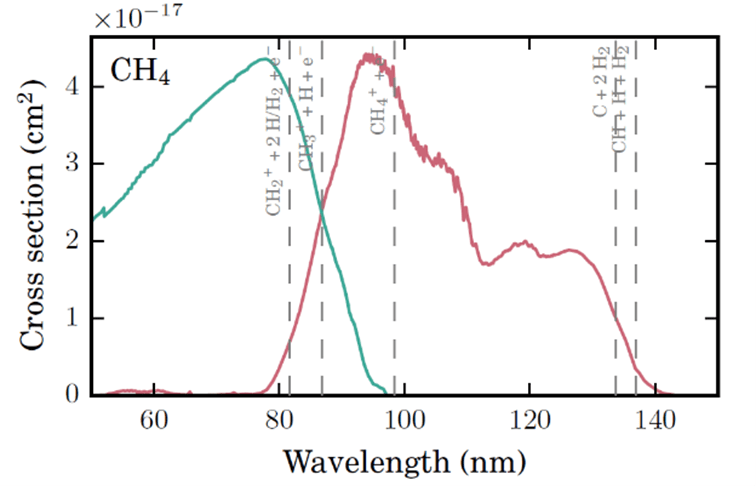

In space, ultraviolet radiation acts as the ultimate destroyer and creator. Ultraviolet radiation is capable of destroying molecules but in doing so it creates reactive species that drive forward chemistry. Upon the absorption of a ultraviolet photon (or UV light) there are multiple things that can happen; primarily molecules either dissociate (break apart) or the ionize (lose an electron). Hence, there are different types of cross sections that describe these various processes, e.g., photoabsorption cross sections, photodissociation cross sections, and photoionization cross sections. The Leiden UV database collects all three for over a hundred molecules of astronomical interest.

These cross sections are necessary for astrochemical modeling because they are used to calculate photo-rates, i.e., how long molecules can survive on average in a particular radiation field before succumbing to the effects of UV light. These rates tell us how quickly (or slowly) certain fragments or ions are formed, and since these fragments and ions catalyze further chemistry, the photo-rates tell us how fast (or slow) the photo-initiated chemistry in space can be.

This can be done by calculating the overall between a particular cross section and the radiation field in question (radiation fields are different in different regions, for instance, the solar radiation field significantly differs from the interstellar radiation field.

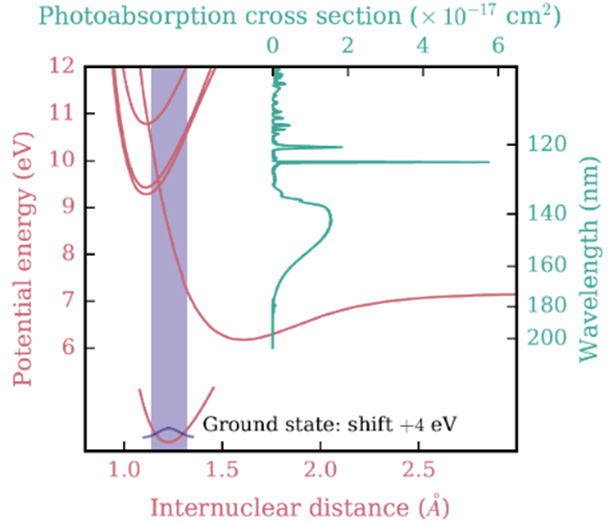

The cross sections themselves are a reflection of the likelihood that UV light of particular wavelengths can dissociate or ionize the molecule, but this is dictated by the molecule’s electronic structure which is often described with potential energy curves where each curve represents a particular electronic configuration (roughly, but not really). The cross sections then (roughly) become the wavelength-dependent overlap of the ground state potential curve with the excited electronic states.

Measuring or calculating these cross sections is a huge challenge and is there are still many cross sections of important molecules that are not well constrained. This can be because of experimental difficulties of preparing samples (a lot of these molecules can not be purchased commercially and thus have to be prepared with complicated experiments), or difficulties with calculations, but describing electronically excited states with quantum chemistry is one of the major challenges in the research field still today.

(Above) Potential energy curves for the ground and excited state of O2 (red) and the O2 photoabsorption cross section (green) shown on equivalent energy and wavelength scales. The shaded region shows the vertical excitation (Franck-Condon) region. (Below) Example of how VUV cross sections comprise both photodissociation (red) and photoionization (green) components which are wavelength dependent. Example of methane (CH4) is given. Various photodissociation and dissociative PI thresholds are given with gray dashed lines. Figures adopted from Heays et al. (2017).

In the case of SH mentioned above, the newly measured cross section was significantly larger than what was previously assumed and recent models of the photochemistry in so-called photodissociation regions (PDRs) in the Orion molecular cloud have shown that the new cross sections and updated photorates lead to an increase in the abundance of the SH+ cation (the result of the photoionization of SH) by a few orders of magnitude. It is thus of great importance to have well-constrained photo-rates (and hence cross sections) to understand photo-induced chemistry in space.

(Blue) Measured photoionization cross section of the SH radical, from Hrodmarsson et al. (2019). (Green) Previously assumed photoionization cross section of SH, from Heays et al. (2017).

(Left) The Orion molecular cloud which includes one of the best-studied photon-dominated regions (PDRs). (Right) Results of a chemical model of the sulfur hydride chemistry in the Orion PDR using updated photo-rates, including the new SH cross section observed above. Figure from Goicoechea et al. (2020).

A lot of progress has been made but there are still many cross sections missing for a complete picture of the photochemical activities of molecules in space. This is a particularly exciting research avenue, and this database update is hopefully just my first step toward filling in the blanks.

References:

Goicoechea et al., Astronomy & Astrophysics (2020)

Heays et al., Astronomy & Astrophysics (2017)

Hrodmarsson et al., Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics (2019)

One thought on “My Marie Curie Individual Fellowship (2019 – 2021(2)) – Part 2 of X, X = 3-5”