I have been reflecting quite a bit about my journey into the scientific discourse. (The word contretemps comes to mind.)

I did my PhD in Iceland in chemistry, but more precisely the electronic spectroscopy of diatomics; investigating perturbations and state mixings where the so-called Born-Oppenheimer approximation breaks down. It’s complicated, has weird connotations, and to me, it is unendingly interesting and mysterious which is why I loved it.

However, my experience dealing with the scientific community gave me the impression that there was an undercurrent of… dare I say… snobbery. Because it was fundamental research. I quickly lost count of how many times I was asked the dreaded question: ”Yeah, but what is the use?“, “What is it good for?“, “How are you going to sell it?“

To be brutally honest, this always made me feel as if I was misplaced and not really accepted. As someone who was (and still is) very driven and ambitious, I knew that if I were to go all the way and make it in the academic world, I would need to eventually go abroad and get a postdoc position somewhere at distinguished institutions and show I could make it in the outside world. This led me to becoming a bit of an opportunist and grabbing every opportunity I was offered to do something ‘extra-curricular ‘, as it were. I joined the board of the Icelandic Chemical Society and became its youngest ever president while I was still in my PhD. I taught a lot. Not just in the university, but privately as well and ended up tutoring over a hundred students over the course of a few years. I got involved in politics and was on the board of the youth organization of the Icelandic Pirate party for a few years. I organized a conference for the Icelandic chemical society. And this is all something I did whilst also pursuing my PhD. Mainly because the feeling I got from people around me was that if I was doing fundamental research, I basically needed to have an immaculate profile in order to simply have a chance of getting a postdoc abroad because my work was useless. (I will skim over the fact that I was also playing in three black metal bands on top of everything.)

I remember that when I gave a seminar about my PhD work at the Science Institute at the University of Iceland, my PhD supervisor asked me the question: “So what could this be used for?“

My PhD supervisor was (and still is) a staunch defender of fundamental research. In his own words: Knowledge breeds knowledge and innovation is only achieved by complete understanding of the underlying principles. I agree with this. Up to a point, given our current academic climate.

In my academic career I have also learned that if you are innovating something and you want to apply it, more often than not you have to do it yourself.

But that is not the point I wanted to make right now.

To answer my supervisor‘s question in front of the rest of the faculty I gave the best answer I had at the time. I had been giving this quite a bit of thought since most of the people I spoke to about my work all seemed to ask the exact same question. I gave my answer from a couple of different perspectives. Firstly, you can make a tenuous link with other fields such as astrochemistry that are interested in the rotational energy levels of multiple molecules and the study of excited states where the Born-Oppenheimer approximation breaks down is still one of the major challenges of quantum chemistry.

But then I also gave the egocentric answer. The real application of my work… was I. Something that people always seem to forget about…is people. What is the use of your work? Am I not enough? My training? Are you going to judge me on my thesis alone? Is that where my career ends and what will end up judging the rest of my career? Am I only worth as much as how much use can be siphoned out of my thesis?

I didn‘t use this wording when I answered the question. I said something along the lines of: „In science we don‘t know what the students are going to do in future. Whether they stay in academia or go join the industrial workforce or something else. The biggest application of my PhD is me, and the biggest application of anyone‘s thesis is themselves.

I‘d like to think that I had given a fairly adult answer, but I didn‘t feel much of a response from the rest of the faculty. Certainly no one ever wanted to talk to me about science policy, about the good of fundamental research. The senior faculty never asked me about the application of my work. At least, not that I can recall after giving that seminar.

I think it is fair to say that I academically grew up in Iceland with big dreams of making it on the big stage of astrochemistry. I felt frustrated because I wanted to write about stuff I loved and that was why I started this website in the first place. I also felt like that the science I had done simply wasn‘t enough so I had to work extra hard in order to be noticed. Me being curious and interested in weird things was never going to be enough.

Let’s fast-forward several years. I ‘escaped‘ Iceland almost six years ago.

In a strange way, I have been haunted by my years during my PhD because I have been trying to prove to the world that I am capable of doing something “useful“. That I am not only tackling fundamental science, but directly applying it as well. This was one of my biggest incentives of updating the Leiden VUV cross section database, i.e., to show that I am capable of doing measurements of things of interest to the astrochemical community and, additionally, I have the capability to drive the application itself and be this fluent link between experimental and modeling astrochemical communities.

I do not consider this to be a bad thing in any way, mind you. But here comes the real incentive to me writing this particular piece.

I started re-reading the Spectra and Dynamics of Diatomic Molecules by Robert Field and Helene Lefebvre-Brion (RIP). This was my bible during my PhD and my go to reference while I wrote my thesis. I also started fetching all of the old papers referenced in the book so I have basically started building a library of old spectroscopy and theory references that I imagine was a good chunk of the reference library of one of my biggest scientific influencers, Robert Field.

In the Reference list of the Introduction there were a few papers by the legendary Nobel Prize winning spectroscopist, Gerhard Herzberg (whose books I also read during my PhD) from the 1960‘s and 1970’s.

To my somewhat surprise, there were not only spectroscopy papers that popped up in my web of science search results.

This piqued my attention. What did Herzberg, a Nobel prize winner for his spectroscopy work, have to say about bureaucracy and science policy?

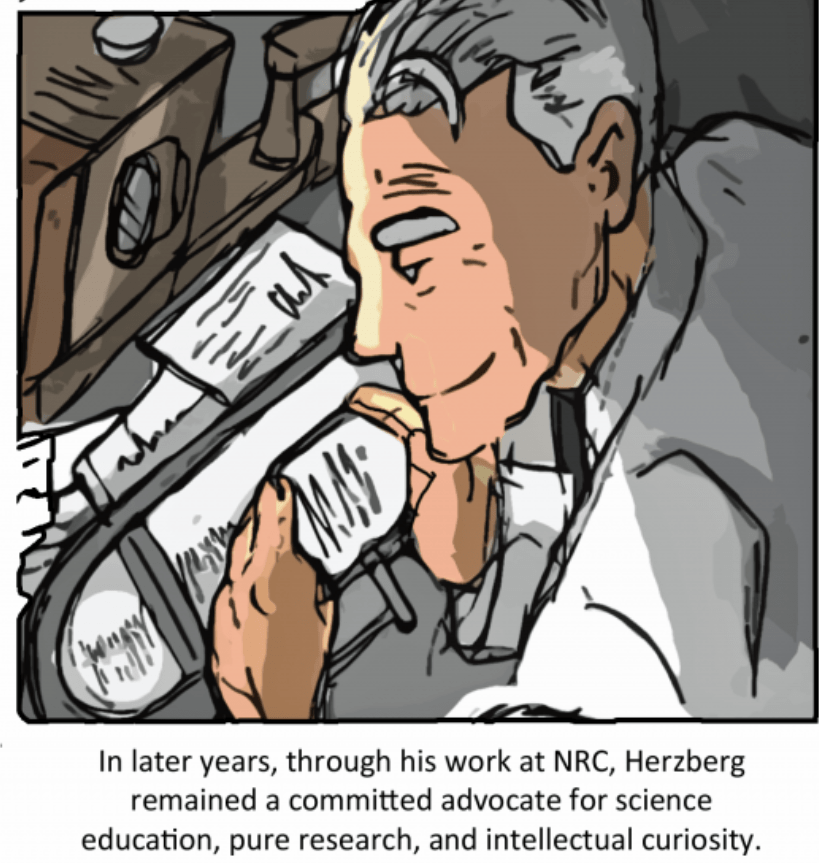

There is actually a brief illustrated history (5 min read) online that summarizes Gerhard Herzberg‘s life and his contributions much better than I could ever. In fact, here is a website with some invaluable insights into Herzberg‘s lifes work.

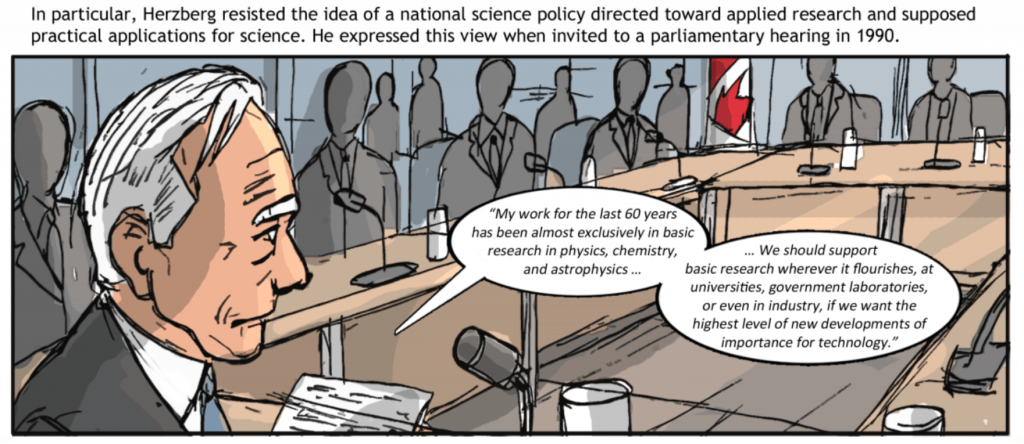

From the illustrated history though, there are two panels that I want to highlight that are near the end.

Herzberg recognized the importance of pure research. Intellectual curiosity. It is a primary driver of the human race. He felt a responsibility and duty to advocate for the independence of scientists from political and administrative restrictions. He further asserted that pure research pursued only with the intent of advancing scientific knowledge (as opposed to technological applications) must be supported financially by the state. While discoveries arising out of basic science research could lead to technological applications at some point in the future, Herzberg more importantly viewed basic science research as vital to our ‘human heritage’ much like art and literature.

Weighing in on the debate of shifting focus from basic research to applied research Herzberg wrote: „There are clearly two principal reasons for the support of pure science in Canada, and elsewhere. One is strictly mercenary. Experience has shown that pure science represents the goose that lays the golden eggs; it helps applied science and technology in their development as I have tried to exemplify by the examples given earlier. Many people do not seem to appreciate this point fully. The other reason for support of pure science by government funds is that scientific research of the purest kind is an intellectual activity which, just like art, music, literature, archaeology, and many other fields, helps us to understand who we are, and what is the nature of the world in which we live.“

I can only concur.

Herzberg critiqued science policy. He felt it illogical for government to try to guide science and attempt to predict future applications; that science policy which always sought practical applications was not only short-sighted but damaging to science. He quoted a famous line attributed to the great physicist Michael Faraday. When the Prince of Wales asked Faraday to describe the “practical use“ for his invention, electromagnetic induction, Faraday reportedly replied, “Sir, of what use is a new-born baby“

There are many instances in science where a discovery‘s practical application are not observed by the discoverer. The technology that led to masers and lasers can be traced to research that was abandoned by the Bell Telephone company. Until his death in 1937, Ernest Rutherford, the father of nuclear physics, did not believe that nuclear energy would ever be useful. Herzberg noted rightly that if even the scientists could not anticipate the applications of their discoveries, what chance do government bureaucrats have?

Hear hear.

But is it already too late? Are we past the point of no return? Is the system already too broken? Modern science has a problem with an over-emphasis on application and using arbitrary indices to estimate the ‘quality of research’ to give out funding. Can we reward creativity in modern research?

Maybe I was on to something during my PhD. Maybe my curiosity is enough. A good scientist is not made by a large h-index or a number of citations. However, those things are definitely helpful in our current system in order to get funding for our research. Funding allows us to build new experiments. Get students to mentor and train.

I don‘t know.

What I do know is that through a lot of trial and error, learning and unlearning, acclimating and reacclimating, and finally putting my focus on where it is important… I, for one, have found that I can do science and still be happy.

To look at it ambitiously, maybe if I learn to survive and thrive, perhaps I can make changes, however incremental, to a broken system in some way. Maybe.

So what is it that I‘m working on actually good for?

It‘s for the good of humanity, you absolute twat.