Back in 2019 when I was in my final year as a postdoc at the SOLEIL synchrotron, my research output started to explode a little bit and I wrote about some of my research successes then. I figured I‘d write kind of a follow up to that post because it seems that 2024 has been the year where a lot of older projects have now finally come to fruition after an appropriate lengthy fermentation process.

I wanted to briefly write about a couple of projects because I am very fond of them and I am exceedingly pleased to have them finally published.

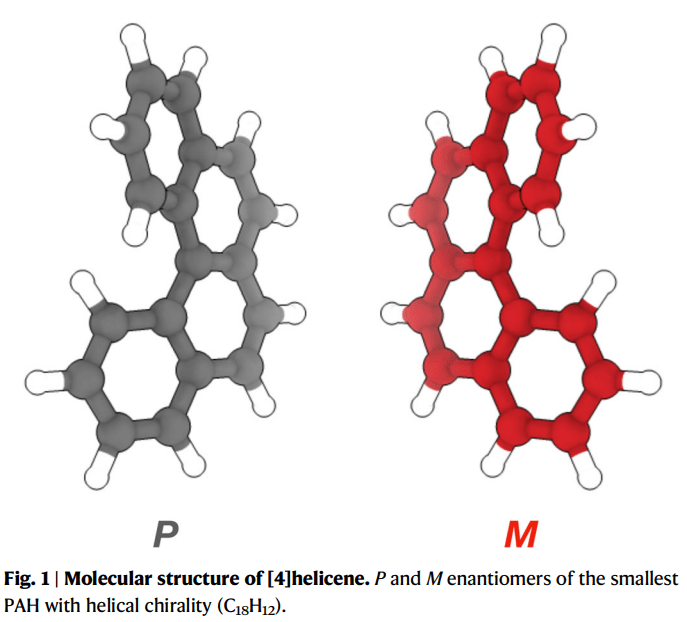

The first work is on the cluster of so-called [4]helicene molecules. Helicenes are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) which I have written about previously (link Marie Curie stuff) but helicenes are really neat and interesting for another reason. Just to clarify, the number 4 in [4]helicene is the number of hexagonal benzene rings in the molecule, and [4]helicene is the smallest helicene which is chiral, i.e., it has non-superimposable mirror images. Which is really interesting because usually when chirality is taught in chemistry classes it is taught from the point of view of a single carbon atom connecting four different groups. However, in [4]helicene there are no such carbon atoms. So how could it be chiral??

Well, because the molecule‘s structure is a helix. Helices are naturally chiral without having a single chiral center per se, like a carbon atom connecting four different groups. Instead the molecules possess axial chirality that still gives them the same optical properties as other chirla molecules of rotating plane polarized light in different directions.

Coming to the paper recently published in Nature Communications, we investigated how [4]helicene molecules cluster together by measuring the ionization energies of the individual clusters containing up to seven monomers. Accompanying the experiments are dedicated theoretical calculations of the arrangements of the monomers into clusters and through the harmony of the two we could show that these chiral PAHs prefer to cluster and stabilize in their homochiral configurations. This could have implications to our understanding of chiral preferences and dust nucleation in molecular clouds in space.

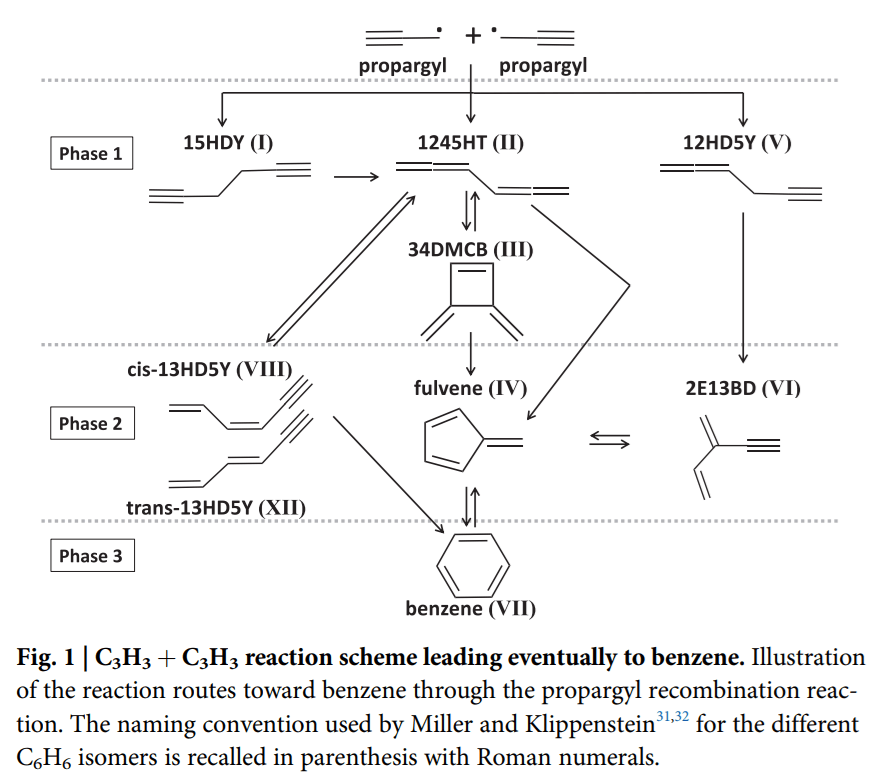

The second paper I wanted to briefly highlight, published in Communications Chemistry, was actually the first SOLEIL proposal I wrote when I started as a postdoc there in 2017, and carried out my part of the experiments in 2018. This paper is also closely linked to PAHs, but here we investigated the formation of benzene with propargyl radicals (C3H3). When two propargyl radicals react, a very complex series of events follow as depicted in the reaction scheme here below.

There are multiple intermediates that can be formed, and they will isomerize back and forth and back and forth until eventually forming benzene, as well as all the other stuff. What we managed to do was to identify all of the reactive intermediates as well as benzene and measure their yields. As this reaction is one of the most important in the formation of benzene, it is important to have laboratory results to verify outcomes of thermochemical models that are principally used to predict the formation of benzene and PAHs not only in space but also in hotter combustion reactors (like when burning fossil fuels).

The reasons for why these projects have taken so long to come out simply has to do with the fact that there are complications that arise when analyzing your data and then you need further input. In the case of the helicenes, it was checking and rechecking the analysis of the experimenta data to check if itwas appropriate and that our conclusions we could draw from them were correct. And this led to a back and forth and back and forth with the theroretical computations.

For the propargyl recombination, after the experiment and when starting the analysis we realized that many of the threshold photoelectron spectra (or photoelctron spectra) we wanted to use to identify all of the products, were simply missing or of insufficient quality in the literature. So, some had to be synthesized and measured and remeasured, and then the results were analyzed and reanalyzed… you get the point.

I think the bottomline here is that sometimes good things require a lot of time, energy, and concerted effort to come to fruition. Science is not just about doing experiments. Subsequently you have to then keep checking yourself, re-checking yourself, and re-re-checking yourself and re-re-re-rechecking yourself. Science is self-examining and difficult and when you have a lot of experts working in tandem to resolve some fundamental riddle, it will take time. Good things usually do.